I did a series of three Facebook posts for the 243rd anniversary of the crossing of the Continental Army at Parker’s Ford in East Coventry/West Vincent Townships in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Because of the size and my level of interest in this event, I decided to create a specifically page dedicated to these posts.

September 19th, 1777 – Prelude

“At dawn, broke camp and crossed the Schuylkill at 2 P.M., at Parker’s Ford (Lawrenceville), where we had to strip to wade. Reached the great road to Reading, passed Trappe, crossed the Perkiomen, on the eastern bank of which we camped. Through false alarms we got no rest, tho’ after such fatigue rest would have been very agreeable.” – Diary of Lieutenant James McMichael, of the Pennsylvania Line, 1776-1778.

243 years ago, September 19th, 1777 was a milestone in the Philadelphia Campaign. The crossing of the Schuylkill River marked the end of offensive maneuvers against the British Army leading to the fall of Philadelphia. It is notable as the day Washington wrote several correspondences, including to John Hancock appraising Congress of his current situation. That day he also writes to George Clinton where he hints that it is likely he will not be able to prevent the British from taking Philadelphia. What looked like a well-planned outflanking maneuver by Washington delayed the British advance only a few days.

Washington’s move also exposed General Wayne and Smallwood’s forces on the British far left flank and rear. This was a significant threat to Howe’s army, but as well see in a few days the British will drive out what was left of the Continental Army in Chester County.

In Philadelphia on this day, word arrived of the British approach along multiple fords just above the city and panic ensued. The Continental Congress began evacuating Philadelphia to Lancaster and eventually York, PA.

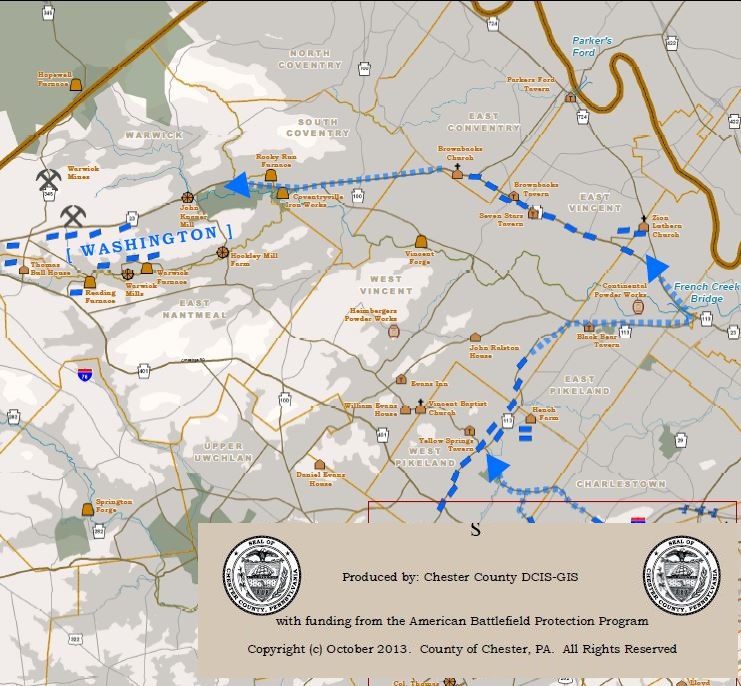

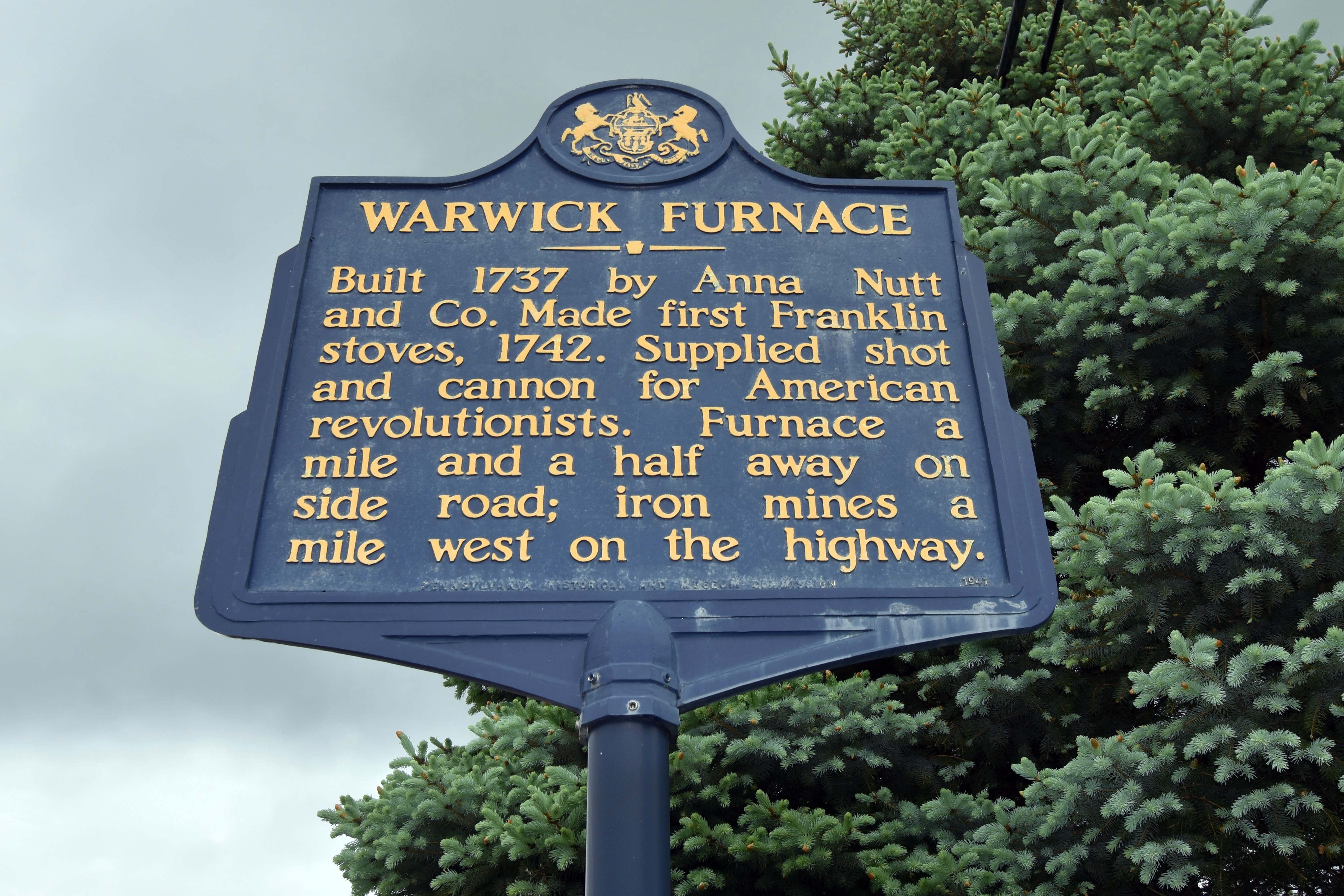

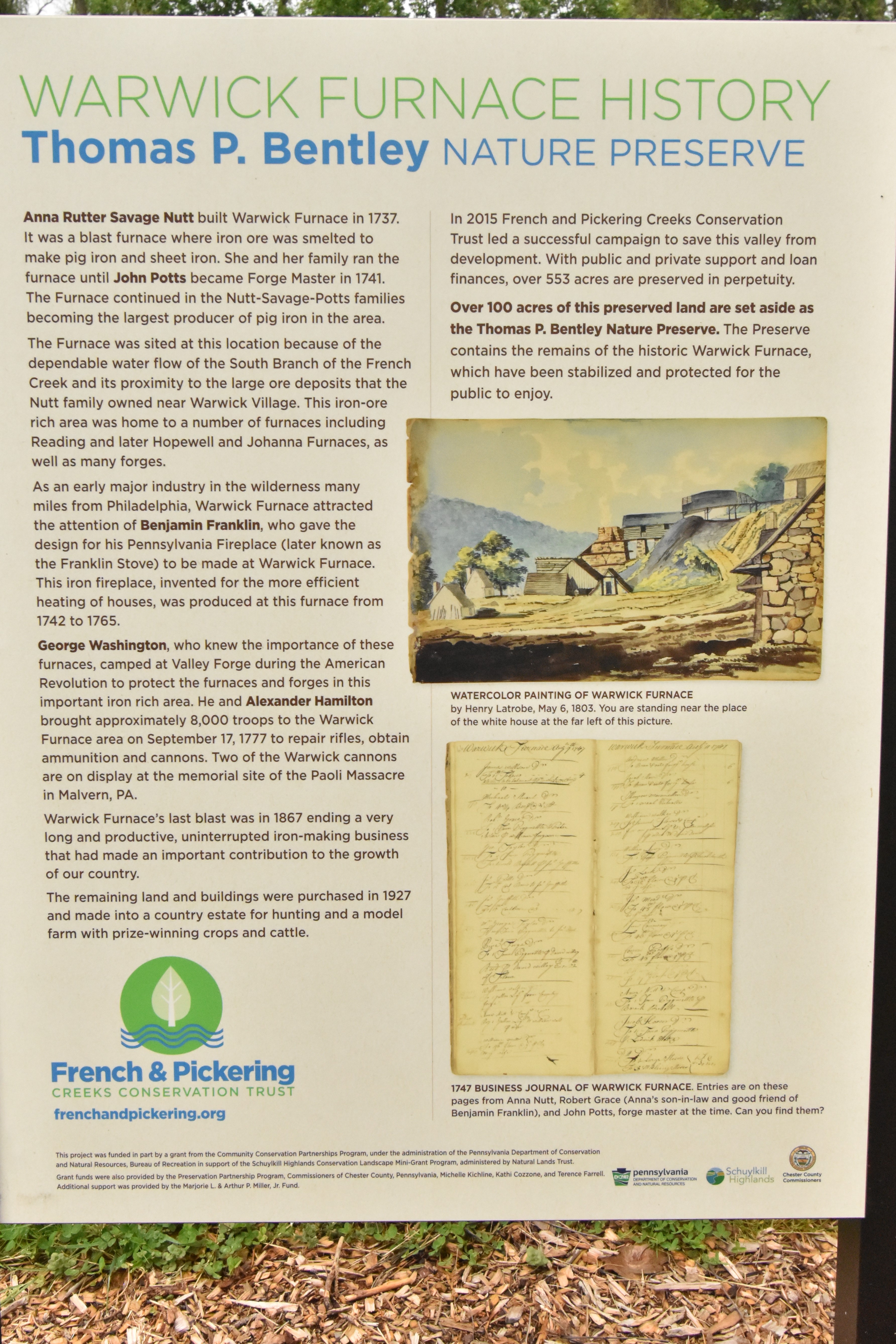

After the Battle of the Clouds on September 16th, 1777, the Continental Army numbered approximately 11,000 men (10,000 regulars and 1,000 militia). The army retreated to Yellow Springs, Chester County, where they spent the night in miserable conditions without tents to protect from the elements. The army baggage and supplies had been left near Valley Forge prior to the battle. Realizing that their cartridge boxes were inundated with water during the downpours and the powder ruined, Washington moved the army next to Reading and Warwick Furnaces in Northern Chester County. Part of the army marched early on the 17th from Yellow Springs to Reading Furnace (a few miles west of Warwick) and the rest joined them at camp in the area on Thursday, September 18th where they took supplies.

Some of the army marched to Warwick by way of the French Creek bridge in present-day Phoenixville and passed by the Continental Powder Works located there (The Journal and Order Book of Captain Robert Kirkwood). By September 1777, the powder mill has ceased production but small arms manufacturing continued. It is possible the Continental Army took what supplies were still there, however earlier on September 10th they began moving powder and guns out of the facility and away from the growing threat of the British Army. It is likely they moved some of the supplies West to the furnaces that were already producing cannon and other munitions (down present-day Rt. 23), and it is reported the powder was moved to Bethlehem.

Both furnaces were actively producing canons and munitions for the Revolutionary War effort. Before and after the war, they continued to be commercial enterprises forging stoves and other metal goods. The Continental Army camped across a several-mile wide area from past Reading Furnace back to Warwick Furnace.

Reading Furnace [Pa.] 18th Sepr 1777 from George Washington to John Hancock: “From the Advices received Yesterday Evening & last Night, It appeared that the Enemy were pushing a considerable Force to the White Horse Tavern, with a view it was supposed to fall on our Right flank. This induced us, to proceed this Morning to this place, where we are cleaning Our Arms with the utmost assiduity and replacing Our Cartridges, which unfortunately were mostly spoiled by the Heavy Rain on Tuesday.”

From George Washington to John Hancock, 18 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/…/Washington/03-11-02-0258. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, pp. 262–263.]

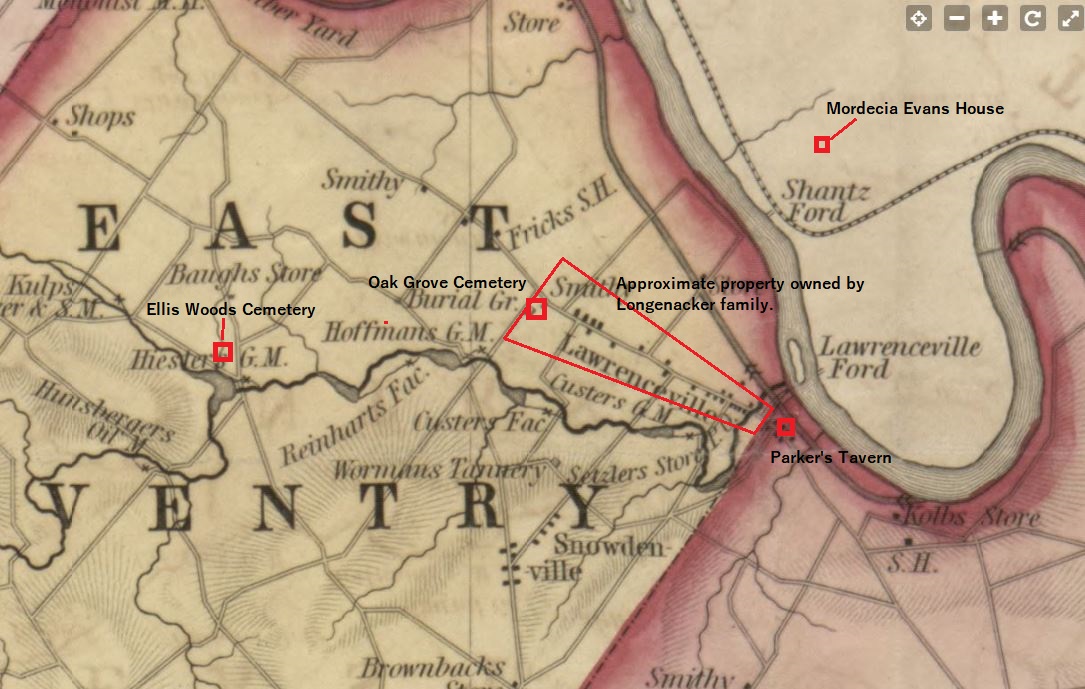

On the 19th, when the army broke camp and departed the Northern Chester County area. They would have traveled east on what is today Rt. 23/Ridge Road and then moved left off Ridge Road towards Lawrenceville, later known as Parkerford, and Parker’s Tavern and ford across the Schuylkill River.

Friday, September 19th, 1777 – Ellis Woods Cemetery

On the 19th, when the army broke camp they would have traveled east on what is today Rt. 23/Ridge Road and then moved left off Ridge Road towards Lawrenceville, later known as Parker Ford, and Parker’s Tavern and ford across the Schuylkill River.

The route the army would have traveled towards the ford and Lawrenceville passes right by the present-day Ellis Woods Revolutionary War Cemetery where seventeen unknown Continental soldiers are buried.

At some time during the Philadelphia campaign, a local barn was used as a hospital and those that died were buried nearby. Some have speculated that it was during the winter at Valley Forge, along with other hospitals that were setup in nearby churches. I’m skeptical of this considering the location along the route of the march; and the following is one of the few references I’ve found:

“Some revolutionary Soldiers buirried on the place of John Hiesters these being men that fel sick when the army crossed at Parkers foard afterwards called Brooker foard and Some died in Longeckers barn and burried in Brauers woods…”

(East Vincent Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania by Frederick Sheeder, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography , 1910, Vol. 34, No. 2, (1910), pp. 194-212, University of Pennsylvania Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20085509)

Local historian Estelle Cremers wrote:

“An 1897 newspaper article relates that ‘on the property of Herman Prize… stands a barn built to replace an old one that was torn down many years ago. This old barn was used as a hospital for the American forces during the Revolutionary War. About 150 yards northwest of the barn, in a small copse of woods belonging to John Ellis, Esquire, are the graves of sixteen American soldiers… About 300 yards north of the hospital, more soldiers were buried; but a public road was laid out through this section many years ago, and the mounds were leveled down to make a thoroughfare right over the patriot’s heads.”

(Coventry, The Skool Kill District, A Basic History of the Three Coventry Townships 1700-1850 but Estelle Cremers and Pamela Shenk, Masthof Press, 2003)

I favor the theory that these were casualties from the march to Parker Ford and were soldiers unable to cross due to sickness or wounds who ultimately succumbed to those. Battle casualties from the Battle of Brandywine were treated or already moved to permanent hospitals setup in Trenton/Princeton, Bethlehem and elsewhere. The two dozen or so battle casualties from the Battle of the Clouds were probably treated at Yellow Springs (although the permanent hospital there was not setup yet). I do not think it is likely they would have traveled with the army. Considering the harsh conditions and long marches from the previous days, I would not be surprised if many the soldiers buried here were not battle casualties but died from fevers, smallpox or other illnesses.

The land where Ellis Woods Cemetery is located was owned in 1777 by John Hiester, a member of a prominent family of early settlers and it may have been his barn referenced as the hospital, although this land was not his primary residence, that being close to the river a short distance away. John Hiester at the time was serving as a captain in the Chester County Militia. He also had two brothers: Daniel Hiester, Jr (from what would become Montgomery County, however was part of Philadelphia County in 1777) who was a colonel in the Philadelphia County Militia; and Joseph Hiester who was a lieutenant colonel in the Berks County Militia. It would be a convenient coincidence if one of the Hiester brothers were travelling with the Continental Army on September 19th and was involved with arranging for the care of the soldiers on John’s property.

The Pennsylvania Militia was commanded by Major General John Armstrong, Sr. and organized into two brigades: the 1st Brigade commanded by General James Potter and the 2nd Brigade commanded by General James Irvine. On May 17th 1777, John Hiester was commissioned a captain in the 1st Company, 4th Battalion of the Chester County Militia commanded by Col. William Evans. Although some writers have assigned William Evan’s battalion to Irvine’s brigade at Brandywine, I’ve been unable to find a specific record of the 4th Battalion, so it’s unclear to me to which brigade they were under. It is also confusing since Col. Evan Evans commanded the Chester County Militia’s 2nd Battalion and only “Col. Evans” is mentioned under the militia returns during this time, being under Irvine’s command.

Most Pennsylvania militia units had been sent by Washington around September 14th to guard Swedes Ford and the other fords along the eastern side of Schuylkill River and prevent a crossing by Howe. However, Washington ordered General Potter to move to Valley Forge to protect the supplies stored at there where he joined Continental Regular General William Maxwell: “General Potter and the balance of his brigade had been sent to the Valley Forge, with General Maxwell’s New Jersey force, to guard the depot of stores at that place.” (The Pennsylvania militia in 1777 : reprinted from the Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, v. 23, no. 3, 1964)

After the Battle of the Clouds, Maxwell and Potter’s armies moved to cover the main army’s baggage and ultimately remove them and some of the supplies (they were unable to remove all stored materials) ahead of the British raid on the evening of the 18th which captured abandoned stores and destroyed the forge.

The connection to John Hiester occurs when Washington assigns Colonel William Evans, commander of Hiester’s 4th Battalion, Chester County militia to guide the baggage from Valley Forge to the Reading and Warwick Furnaces. Evans lived in Vincent Township, just west of present-day Phoenixville and would have been very familiar with the route.

“Yellow Springs [Pa.] 17th Sepr 1777 Sir, I desire you will immediately move the Baggage and Ammunition from the place where you are at present to Warwick Furnace. Colo. Evans, the Bearer of this, is kind enough to undertake to pilot you by the safest and best Rout. No time is to be lost in the Execution of this Business and I think if you were to impress a few Waggons and lighten the others of part of their loads it would be better as the Roads are so exceedingly bad. The Baggage and Ammunition that is at present at perkioming1 is to move up to Pottsgrove. I am Sir &c.” – From George Washington to Major General Thomas Mifflin or an Assistant Quartermaster, 17 September 1777,”

Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/…/Washington/03-11-02-0252. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, p. 259.]

With Potter’s brigade accompanying the movement of the supplies to meet up with the Continental Army over a route being led by Col. Evan’s, it’s very likely that John Hiester was with the Continental Army at the furnaces and was on the march on September 19th that passed through his land in Chester County en route to the ford at Parker’s Tavern.

Estelle speculates that this hospital and others in the area fell under the French Creek Hospitals established in nearby churches, however those were established closer to the time of the Valley Forge encampment. Including the additional graves that were lost, with these many burials, a hospital at the Ellis Woods location would have been sizable. There is no mention of a hospital associated with the French Creek church hospitals (which are all close together, and fairly distant from Ellis Woods) here.

Friday, September 19th, 1777 – Lawrenceville and Crossing the Schuylkill at Parker’s Ford

In September of 1777 the hamlet of Lawrenceville consisted of approximately twenty houses, barns and mills, split by Pigeon Creek and the township line of Coventry to the North/West and Vincent Township to the South/East. The actual ford was just south of where the creek enters the river.

One property owner in Lawrenceville/Parker Ford was the Longenecker (or Longacre, or several other spellings) family located on the Coventry side of the area. As mentioned, Frederick Sheeder wrote that Susannah Longenecker’s barn also saw some Continental Army casualties, and tax records of 1798 list a Longenecker barn on the property.

Widow Longenecker as she became known later also has an interesting tale about her around this time. Estelle Cremers writes about this, and attributes the story to Richard Cryer, a Longenecker descendant. It’s been published elsewhere and for ease, I’m including the text from “Our Immigrant Heritage: Longacre”, Written by Forrest Moyer on November 10, 2017 and published on the Mennonite Heritage Website at https://mhep.org/our-immigrant-heritage-longacre/

His widow, Susanna Parker, received land from her father’s estate at Parker Ford the following year. She remarried to John’s cousin Jacob (Longenecker), son of Ulrich, and she is remembered for a difficult experience during the Revolutionary War. American spies, dressed as shabby escaped prisoners of war, walked along the Schuylkill Road, seeking to entrap British Loyalists. Seventy-year-old Susanna, home alone with a grandchild, and unaware of the danger, offered food and drink to the travelers, as she did to all tramps. The spies then reported her to the authorities in Philadelphia as a British sympathizer. Elder Martin Urner of the Coventry Brethren congregation was similarly tricked.

The sentence handed down against Susanna was draconian, “a fine of one hundred and fifty pounds or in default of payment to receive one hundred and seventeen lashes on her bareback at the public post.” Susanna and her husband Jacob appealed this sentence, with support of their neighbors, and her fine was reduced by a third. Part of the appeal stated that “Jacob Longacre…during the present struggle for American liberty…has been often called on for forage, provisions, quarter, team, and etc., and one of our Hospitals was for several Months at his house…and he contributed on these several occasions as liberally as could be expected from a person who apprehended himself restrained by his religious principles from being actively concerned in war.” (Longenecker Family Newsletter 1:1, pp. 2-3).”

On the south side of Pigeon Creek was the Parker’s Tavern complex which in 1777 consisted of the tavern, a barn next door, three houses and several mills. The ford was likely just east of the tavern, the area now is completely overgrown with trees and brush. It was here that the Continental Army with approximately 8,000 troops including George Washington crossed the Schuylkill onto the east bank and then moved south to defend the other fords across the river being threatened by the British Army.

Several days later, Wayne’s army after retreating to Red Lion from the Battle of Paoli also crossed to join up with the main army.

“The story is told by the folks living the Parker’s Ford at that time is that the weary soldiers took off their clothing, wrapped it around their guns and crossed the river holding guns and clothing over their heads. They had a long march ahead of them and preferred to do it in dry clothing.” (“Limerick Township: A Journey Through Time 1699 – 1987” by Muriel E. Lichtenwalner, Limerick Township Historical Society, Limerick, PA 1987)

An American office, Capt. Enoch Anderson of the Delaware Regiment, described his unit’s method of crossing the flood-swollen Schuylkill: ‘The late rains raised the waters. We entered the river in platoons, – the river was about two hundred yards wide. I now gave orders to link arm in arm, -to keep colose and in a compact form, and to go slow, – keeping their ranks. We moved on, -we found the reiver breast deep, -it was now night as we gained the western shore [left bank] all wet, but in safety.”

“Battle of Paoli” by Thomas McGuire, Stackpole Books, 2000, Page 79.

McGuire insinuates this described the crossing on the 19th, however it is hard to tell the exact date from Anderson’s narrative written forty two years later. But it’s still a good description of what the crossing was probably like. Once across the Schuylkill, the army proceeded down Linfield Trappe Road to the Great Road (present day Ridge Pike, near the Augustus Lutheran Church) and then onto the lower fords before Swedes Ford.

In Limerick Township a short distance past the ford stands the Mordecai Evans house. Owned by Evans in 1777, George Washington stopped here to rest and dry off. While here, he wrote several correspondences before moving on with the rest of the army. Interestingly, his letter to George Clinton seems to show his concern for the current situation knowing that there are many fords where the British can attempt to cross. He likely realized he could not defend all of them.

“Parkers Ford—on Schuylkill Septr 19: 1777 ¾ after 5. P.M…. I am now repassing the Schuylkill at Parker’s Ford (Lawrenceville), with the main body of the army, which will be over in an hour or two, though it is deep and rapid… As soon as the troops have crossed the river, I shall march them expeditiously as possible towards Fatland, Swede’s and the other fords, where it is most probably the enemy will attempt to pass.” –

From George Washington to John Hancock, 19 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/…/Washington/03-11-02-0268. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, pp. 268–270.]

“I am now about twenty five Miles from Philadelphia on the East Side of Schuylkill with the Main Body of our Army, fronting the Enemy, who are on the opposite Side. We have also a Body of Troops hanging on their rear, under the Command of Genls Smallwood & Wayne. I suppose General Howe will soon attempt to pass the Schuylkill, which, unhappily admits of but too many easy Fords.”

From George Washington to George Clinton, 19 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/…/Washington/03-11-02-0266. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, pp. 267–268.]