Head of Elk

On August 28th, the main British army under Howe’s command leave Oldfield Point and following a road which is likely much of today’s Oldfield Point Rd. towards Head of Elk, now known as Elkton. Captain Andre wrote in his diary that day:

“This morning the Light Troops, British and Hessian Grenadiers, 1st, 2nd, and 5th Brigades marched to the Head of Elk. The remainder of the Army under Lieutenant-General Knyphausen changed the disposition of their encampment.”

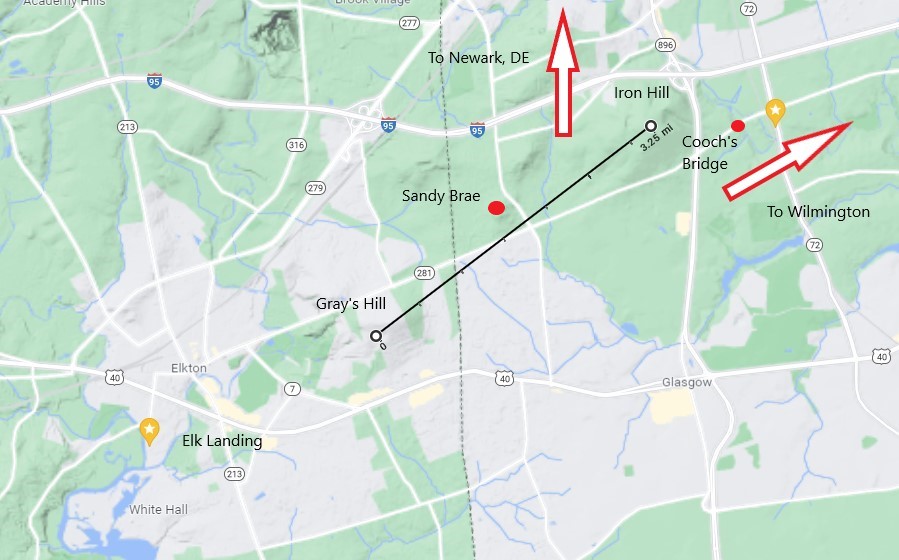

There was very little resistance, the town abandoned, and Howe “supposedly” made his headquarters at the Elk Tavern on the main street at the western side of the town. Later it was named Hollingsworth Tavern and remains today as an apartment building on West Main Street in Elkton. Over the next several days the British army continued foraging for food and supplies in the area and there was the occasional skirmish between British and Hessian troops, local militia and Continental regulars. On the 29th, the British army moved eastward from Head of Elk towards Iron Hill up what is today Old Baltimore Pike. Forward units were posted and camped on Gray’s Hill, which sits between Iron Hill and Head of Elk.

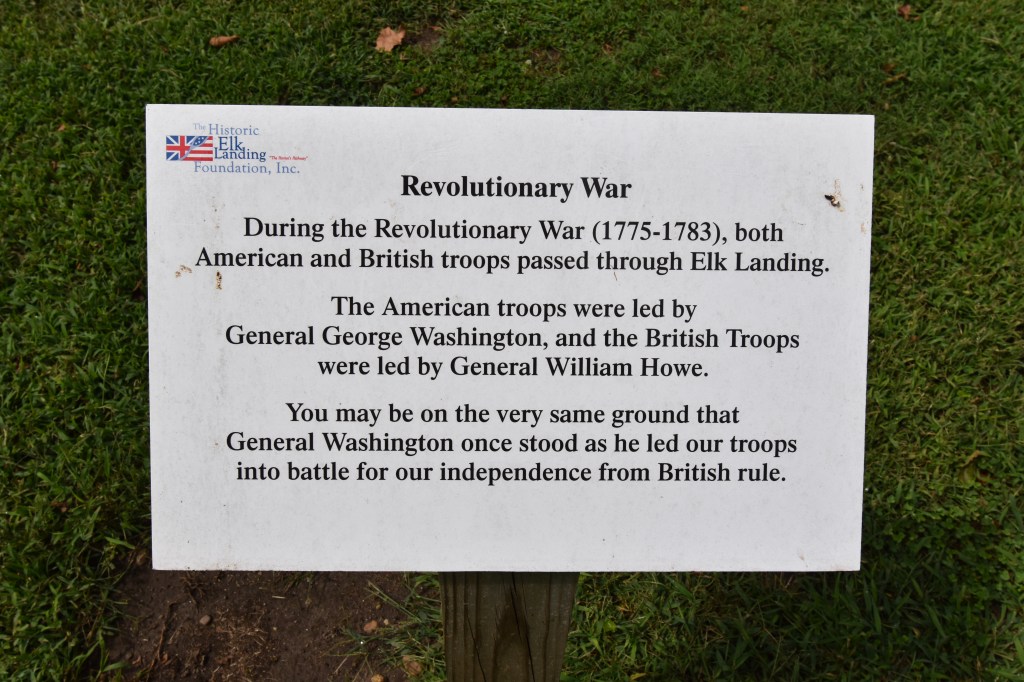

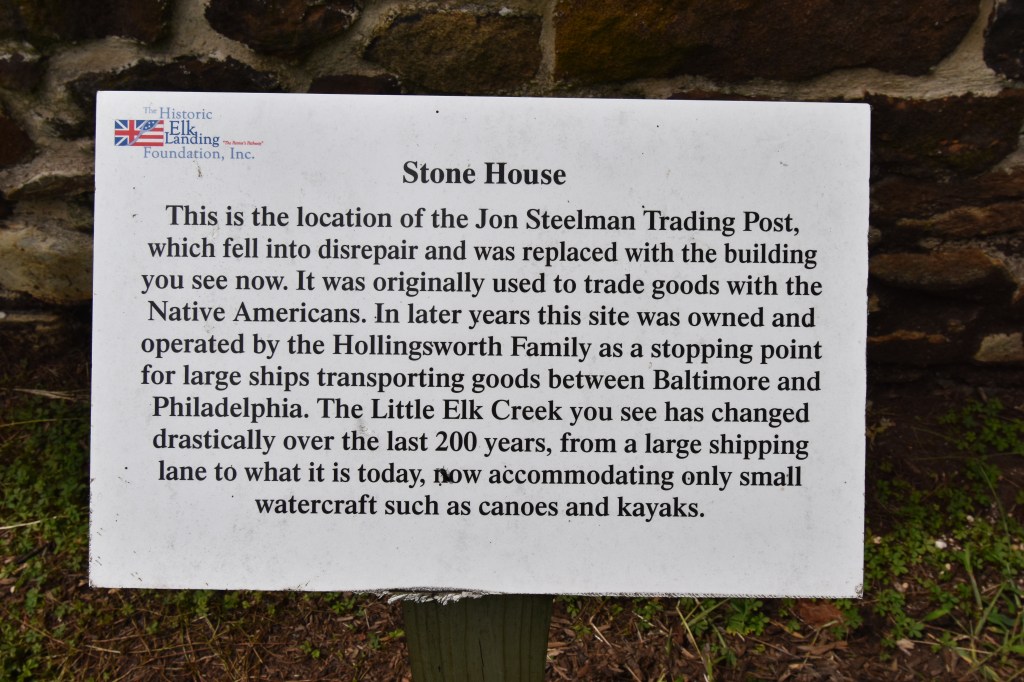

Although not directly a part of the British advance through Head of Elk, southwest of the town sits Elk Landing, just north of the Elk River split into Little Elk Creek and Big Elk Creek. This was the furthest navigable point on the Elk River. Through colonial times, Elk Landing was an important transit and trading hub along the East Coast. Ships would sail to and from there, to Baltimore and further down the Chesapeake Bay. Passengers who were travelling North/South would portage to and from a point twelve miles away on the Christina River linking the route with the Delaware River/Bay. In 1781 both Lafayette and Washington took their armies through Elk Landing on their way south to join the Southern Campaign ending in Yorktown. Besides being a trading post, a shipyard was established in the 19th century.

A good illustration of the activities and Elk Landing is captured by Captain Johann von Ewald, a Hessian officer, who kept a diary, and that day wrote regarding Elk Landing:

“’some twenty ships lying at anchor,’ and he, ‘fired several shots at the people standing on the decks, who immediately made signs for peace with their hates and white handkerchiefs.’ The ships were filled with valuable cargos, including ‘much indigo, tobacco, sugar and wine.’ He reported the find to General Howe, ‘who accompanied the Jager corps.’” – McGuire, “The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume One: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia”, Page 140.

Besides the colonial period, there was much activity during the War of 1812 including several forts built to protect the area from the British. Check out more about Elk Landing and the events there by visiting Historic Elk Landing Foundation at https://www.elklanding.org

Iron Hill

If you’ve never heard of the Iron Hill Brewery – it’s a brewpub chain prominent from the Philadelphia area down to Atlanta, GA and their website has this information: “During the Revolutionary War, a fierce battle is fought atop Iron Hill, outside of Newark, Delaware. Soldiers fight for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness – unaware that in more than 200 years, a group of Delaware locals will exercise that right to pursue happiness by opening a brewery right down the road. They will name it Iron Hill in honor of what the soldiers fought for.” Although I’m not sure how much fighting was done “atop Iron Hill” during the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge, kudos to Iron Hill Brewery and therefore, I am a card-carrying member of their King of the Hill Rewards Club – and I like their beer.

Prior to the arrival of the British at Elk Neck on August 25th, Washington was made aware of the British fleet sailing north and moved the Continental Army from north of Philadelphia down to Wilmington, Delaware and setup headquarters there while he tried to figure out where Howe was headed. After the 25th, the Continental army and several state militias moved into positions west and north of Wilmington to defend against a British advance. The army moved into positions at Christina Bridge, along the White Clay Creek to the northeast and outside of Newark near the White Clay Church.

In addition to these troop locations, a small light corps made up of seven hundred Continental Regulars from various divisions and a thousand militia under the command of General William Maxwell took up positions on and around Iron Hill. According to British reports on August 29th, American troops were visible as far forward as Sandy Brae, another smaller hill located about halfway between Gray’s Hill and Iron Hill.

Prior to the American troops moving into position around Iron Hill, Washington decided to reconnoiter the situation and on the 26th, he rode with Lafayette, Nathaniel Greene and General George Weedon (and perhaps others including dragoons) to the top of Iron Hill. From there, they proceeded to Gray’s Hill, which is about two miles east from the center of Elkton. Thanks to several accounts by both Washington and Lafayette, sorely lacking in detail, a story has developed that Washington could have been easily captured, and they stayed the night in a house at the base of Iron Hill. Lafayette wrote two years later:

“The same day that the enemy landed, General Washington imprudently exposed himself to danger. After a long reconnaissance he was overtaken by a storm, on a very dark night. He took shelter in a farmhouse, very close to the enemy, and because of his unwillingness to change his mind, he remained there with General Greene and with M. de Lafayette. But when he departed at dawn, he admitted that a single traitor could have betrayed him.”

There’s been a lot of confusion about this, and there are multiple accounts that Washington stayed at the Elk Tavern, at Robert Alexander’s home, The Hermitage, and at the unknown farmhouse. Recent research seems to debunk much of this story, and I won’t go into detail here, but please read this very fascinating article at the Journal of the American Revolution that was published on April 16th, 2020, by Gary Ecelbarger: “WASHINGTON’S HEAD OF ELK RECONNAISSANCE: A NEW LETTER (AND AN OLD RECEIPT)” https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/04/washingtons-head-of-elk-reconnaissance-a-new-letter-and-and-old-receipt/

This article also questions the accounts that have Washington either staying at or taking a meal at the Elk Tavern. AND if that wasn’t enough, it also suggests that Howe’s headquarters was not at the Elk Tavern but was at The Hermitage. This wouldn’t be the only time in The Philadelphia Campaign that Washington and Howe almost crossed paths: later in September, Washington stayed/ate at Fatlands, a farm just across the Schuylkill River from present day Valley Forge National Park and within the next day or two, Howe did as well. The story about Robert Alexander is also very interesting.

I also want to mention that the excellent American Revolution Podcast by Michael Troy did an episode entitled: “ARP157 Head of Elk & Cooch’s Bridge” on Sunday, July 12, 2020. It’s a nice overview of the subject and goes into some more detail about General Weedon. Here’s a link to the transcript, and if you are a fan of the American Revolution and you’re not listening to this podcast, you’re missing out:

https://blog.amrevpodcast.com/2020/07/arp157-head-of-elk-coochs-bridge.html

Lastly, the other story about Iron Hill comes two days later on August 28th when Washington was again reconnoitering the situation and rode to the top of Iron Hill. Howe had marched into Head of Elk with little opposition that day, and advanced to Grey’s Hill about 3 ¼ miles away Iron Hill. Captain Muenchausen, another British office who kept a diary wrote:

“We observed some officers on a wooded hill opposite us, all of them either in blue and white or blue and red, though one was dressed unobtrusively in a plain gray coat. These gentlemen observed us with their glasses as carefully as we observed them. Those of our officers who know Washington well, maintained that the man in the plain coat was Washington. The hills from which they were viewing us seemed to be alive with troops.”

Seems the two Generals were sizing each other up.

As mentioned in my first post on this topic, please check out “The British Invasion of Delaware, Aug-Sep 1777” by Gerald J. Kauffman and Michael R. Gallagher. If you didn’t read my first post, go back and do so. Or buy it at https://www.amazon.com/British-Invasion-Delaware-Aug-Sep-1777/dp/1304287165 It’s a great work with excellent maps to guide the reader through the events in Maryland and Delaware, 1777.